The Great Bed of Ware :: An exercise in Interactive Narrative

The main challenge in this project lay in converting a primary story telling piece, the museum artifact, into an engaging community conversation. While I read the text provided to us before the project, one part that caught my eye was, what Lewis Mumford (1960) said about artifacts. ‘From late Neolithic times in the Near East, right down to our own day, two technologies have recurrently existed side by side: one authoritarian, the other democratic’. Most items in a museum come laden with rich history and cultural significance that maybe obsolete now. This sense of alienation (in time and culture) is heightened by further encasing the artifacts in glass boxes. Thereby creating distance between the observer and the object. To induce an interaction stemmed from the narrative of the object was an exciting prospect. The main question was how do we make the visitors curious about the object. Curiosity has been recognized as a critical motive that influences human behavior (Loewenstein, 1994). Playing on this idea and the idea of Gestalt psychology, we devised an interaction that was based not only on curiosity of the person but also on his/her beliefs. The artifact that we chose was the Great Bed of Ware. Bed as a concept borderlines between the realms of the physical and the spiritual. A sort of plane of transference between two states of being.

‘Symbolic Anthropology’ was a term that I came across while researching on ghosts and why people believe in ghosts or spirits. It views culture as an independent system of meaning deciphered by interpreting key symbols and rituals (Spencer, 1996). The major premises governing symbolic anthropology is that ‘beliefs, however unintelligible, become comprehensible when understood as part of a cultural system of meaning’. As Roland Barthes (1957) puts it, myth is a metalanguage. It turns language into a means to speak about itself. We used technology as a metalanguage for the construction of our narrative. The interaction takes place in the ambiguous space of real and hyper real and uses the observers’ personal experience as an interface to gauge the success of the interaction. Thinking back, I don’t suppose I would change anything about the designed interaction. It was a perfect blend of technology and spiritual beliefs. An extension of it though, could have been a deeper study of semiotics and symbols that were found on the bed. Not only was the bed marred with carvings and amulet stamps from its various users, the wooden ornamentation suggested the origins and the aspirations of its maker. It would have been interesting to study the four-poster bed as a concept of private space within four walls of a room.

The bed with its illustrious past had played host to many a party of men and women spending the night on the bed at one time. Stories of the secret life of the bed immersed, as a host for orgies and sexcapades. During the initial brainstorming and research for the project, we came across a very interesting story about the bed devoid of any such sensual connotation. It was believed that when the maker of the Great bed of Ware presented the bed to King Edward IV, he was so impressed that he blessed the artisan with a lifetime of compensation. But soon after the death of the maker, the bed found itself in traveling through inns. So enraged was he, that his masterpiece (meant for the royals) was now being used by lowly commoners, that his ghost would haunt the sleepers of the bed. Users complained of being thrown off the bed, tickling and waking up with scratch marks all over them. Though not much truth can be found about this story, we really liked the idea of this historic piece being haunted. It is a sort of expectation that you have about old items.

The bed has been a celebrated piece within the museum (Victoria & Albert Museum, London) because of its grandeur and stature. We noticed, many tourists taking pictures of themselves with the bed as a souvenir of their travels. Taking our idea of the unexplained forward, we decided to use a camera lens as an extension of the human eye. Photography as a mode of documentation. A simple image clicked in front of the bed reveals more than what is visible to the naked eye. A photograph is always invisible; it is not it that we see (Barthes, 1980).

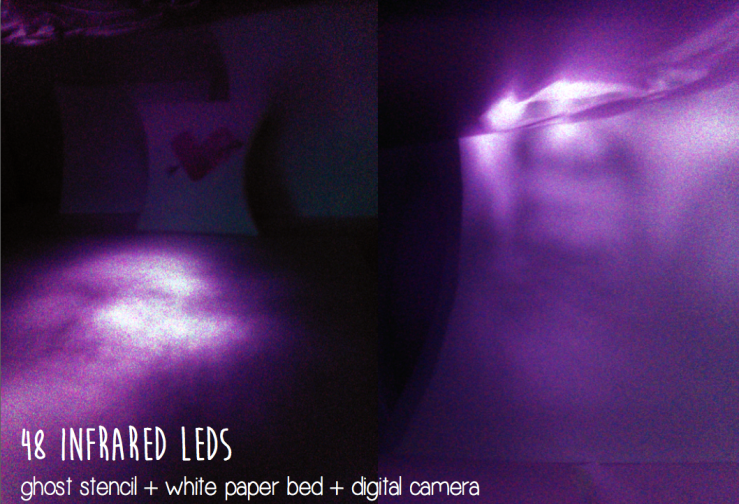

Through our project, we wanted to question the idea of technology as an extension of the human body. By McLuhan’s (1964) theory, pencil becomes an extension for the hand, wheel becomes the extension of the legs, and the camera becomes an extension of the human eye. To challenge the idea we took to physics. Scientifically, the human eye can see a negligible portion of the light spectrum, between 390 – 700 nm. Light frequencies that are either too high or too low for humans to see are ultraviolet and infrared, located just past the red portion of the visible light spectrum. CCD cameras, on the other hand, are able to ‘see’ outside of the human visible spectrum. Using this phenomenon we devised a method by which a shadow is cast onto the bed using infrared light. To passers by this light and the subsequent shadow remain invisible; devoid of any interaction. But as soon as the user takes a picture or views the object through the camera lens, a shadow appears on the bed. What we hoped to achieve through this was this feeling of surprise, of momentary confusion, of awe. For observers who believed in spiritual existence, it was a sighting and for people who didn’t, this was a way of dismissing the theory. We really wanted the element of playfulness to be present in the interaction. The unexplained intrigues people and humor is a good way of diluting the seriousness of the matter. Documentation of the project happened mainly though photographs taken via mobile devices and tablets. A part of the simulation was created via animation. Documentation of the creative processes took place in the form of paper prototypes and experiments with lights of different intensities.

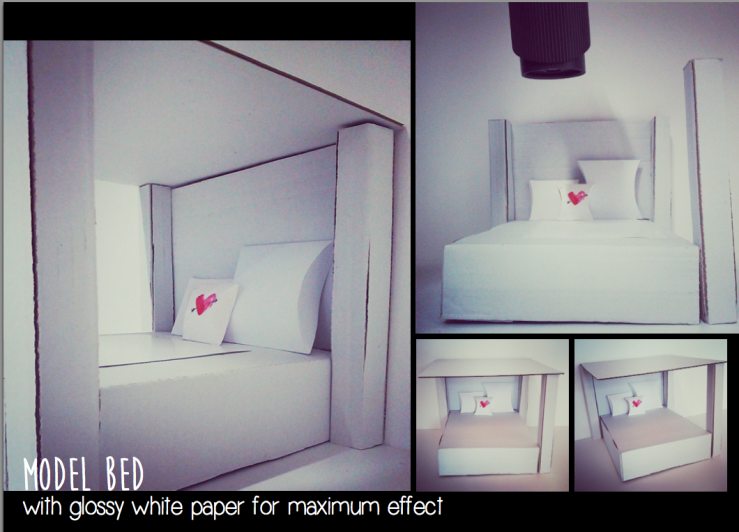

Since the main idea of the project (that of ghost imaging) remained the same, different approaches were explored for concept representation. Playing on the belief that, looking at oneself in the mirror right out of bed leads to the soul exiting the body, we planned to devise an interface which, when a person took a ‘selfie’ in front of the bed, would produce an inverted image of the person’s face into the picture. This was to be done via a positioning sensor and face substitution. But this seemed a far stretch from the actual narrative of the Bed of Ware. The other approach was to have infrared projections onto the bed simulating the existence of the spirit. But, since projectors do not project infrared light we resorted to looking at other sources. The development of this idea had its humble beginnings with 2 5W infrared LEDs borrowed from Nicolas. The light given out by them was negligible. We realized we needed an infrared bulb of high intensity and thus began our weeklong search of an infrared light source. Though the production of infrared light is not uncommon, its main usage is as a heat producing, pain-relieving device, in the medical field. Many online purchases and returns later, we decided to use a CCTV camera with night vision as our source of infrared light. Equipped with a dark room, a night vision CCTV camera, a paper stencil of an Edwardian male face, a mock up of the bed in super white glossy paper (we realized the shadow cast on any other surface was faint; the light was being absorbed by the surface), we began our experiments with invisible light. After some initial hiccups of gauging the right distance between the light, stencil and the bed, we were able to achieve a middle ground.

The intention behind this narrative project was an organic interaction that compelled the users to look at the artifact in new light (and literally so!). Though for this project augmented reality would have been a good approach, we wanted to produce a piece of work that was achievable given the time frame and expertise. Early on, the idea of weaving the infrared LEDs into the fabric of the sheets, hiding the electrical circuit was discussed and later dismissed, since it over complicated the project. We also debated having the light source dangle oscillate under the canopy of the bed so that when captured as a still image it would not have distinct outlines but be a cloudy blur just as how ghosts are generally perceived to be. The brief called for the use of a tablet device in front of the artifact. We wanted the interaction to be as organic and spontaneous as possible. Though a tablet fixed in front of the artifact warrants an immediate curiosity from the observer, (plaques and information boards are a common phenomenon in museums) it could result in the drop of the ‘wow’ factor. The audience would then expect for something to happen. The idea was to keep the interaction as organic as possible by concealing technology and have the spiritual beliefs of individuals play as a layer of interface.

The major setback of our project was the unavailability of infrared light bulbs. When looking for the bulb in stores around London yielded no result, we ordered a 250 W (which we’d presumed to be strong enough) bulb from the Lightbulb Company but that turned out to be an infrared heat bulb. We then got a CCTV camera with night visibility up to 8 meters. Unfortunately the LEDs were not strong enough to produce clear images. Some research and consultation later we found a CCTV camera with 48 LEDs that had visibility up to 40 meters. This was the strongest source of light found. Though this solved the problem partially, the light emitted needed to be collected and concentrated to achieve maximum result. With our lo-fi approach to the whole project, this was prototyped with a piece of mirror. A convex lens or a Fresnel lens would have been the ideal solution. Given the progress and constant setbacks in the project, we debated going back to the initial idea of using a Max patch to create mirror ghost images of the users. But the idea of using infrared light and creating this ambiguity between existence and non-existence (technology induced twilight state), seemed like the better idea. Using science to draw a fine line between representation and abstraction. As Gary Davis described John Smith’s work, ‘Smith signals a chiefly associational system, which deftly manipulates the path of our expectations.’ Quintessentially, the same reaction we’d hope from our audience.

The first points of references were Ectoplasm (Richet, 1923) photos and Pepper’s Ghost. John Henry Pepper (17 June 1821 – 25 March 1900), who popularized the effect of creating a ghostly image in a 3D space using Pelxi-glass and lighting, was a good starting point. Ectoplasm is said to be a substance or spiritual energy ‘exteriorized’ by physical mediums. Though the existence of genuine cases is debated, this sort of photo-manipulation served as an early idea and influence. The Image Fulgurator by Julius Von Bismarck was an excellent study for this project. It intervenes when a photo is being taken, without the photographer being able to detect anything. The manipulation is only visible on the photo afterwards. Though the idea was almost similar the technology suggested/used was different. Audun Mathias Øygard’s experiments in real-time face substitution were another body of work that influenced the outcome of this project. Works of Hellicar and Lewis, who make the audience an active part of the interaction greatly, intrigued me. Their projects like the ‘Hello Cube’ and ‘Night Lights’ have a curiosity inducing playfulness. This makes the outcome more engaging. Created by Thyra Hilden and Pio Diaz, ‘Forms of Nature‘ chandelier is a beautifully designed bundle of white tangled branches, casting shadows on the walls that look like forest trees.

If there were anything I could change about the project, it would be to trigger the infrared shadow just as the picture is taken, much like the Image Fulgurator (Von Bismarck, 2008). Not have the intervention be seen via the camera lens but only after the picture taken. That would have added another layer of ambiguity to the project. There is certain romanticism about finding something hidden in a photograph, something you hadn’t seen before. Another change that can take this project a few notches up is the use of augmented reality. Use the tablet device to allow a digitally enhanced view/perspective of the artifact.